No apologies for Project L.E.A.R.N.

CREDIT: STEPHANIE LAI

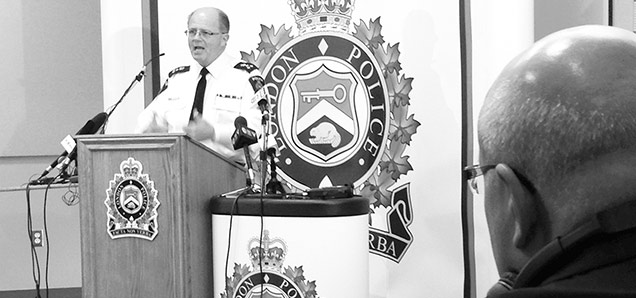

CREDIT: STEPHANIE LAILondon Police Chief Brad Duncan addressed the press about Project L.E.A.R.N. backlash and plans to move forward.

It was a typical day in early September. Corporate Communications and Public Relations student Priya Das had finished a day of class and was hanging out in her Fleming Drive townhouse, chatting on Skype with her boyfriend. The quiet afternoon was interrupted by a knock at the door.

“I was the one who answered the door,” she recalled. “I was obviously taken aback, because it was a police officer in uniform.”

Like other residents living in student-heavy areas, such as Fleming Drive and Thurman Circle near the College, Das and her three female roommates were asked for identification and a list of personal information — their names, ages, birth dates, student status, and parents' names and addresses — even though they hadn't done anything wrong.

This door-to-door initiative fell under the umbrella of Project L.E.A.R.N. (Liquor Enforcement And Noise Reduction), an annual education campaign run in September and April by the London Police Service that cracks down on rowdy behaviour.

“There wasn't much of an explanation as to what Project L.E.A.R.N. is, it was kind of explained in passing,” Das said. “There was no mention of why it was called Project L.E.A.R.N. or what they were trying to learn about. It was very vague.”

London police faced backlash after word of the door-to-door information-collecting initiative spread.

Adam Gourlay, president of the Fanshawe Student Union, which partners with the police for Project L.E.A.R.N. each year, was troubled after hearing complaints from students and their parents about the tactic. “Because we are partners in Project L.E.A.R.N., we should have been notified that this was going to happen where they were going to talk to students and ask for information when [students] didn't do anything wrong.”

The Student Union does its part to inform students about London's noise and nuisance bylaws before party-heavy times of year. The executive team goes door to door in student neighbourhoods to hand out flyers in September and April and during holidays like Halloween and St. Patrick's Day. On the backs of these flyers is a list of on-campus events where students can have some safe (and legal) fun.

After a strong negative reaction to the information-gathering tactic from students and their parents, student leaders from Fanshawe and Western University and even some local lawyers, Police Chief Brad Duncan said he would be conducting an internal review. At an October 26 press conference, Duncan announced that the London Police Service will destroy the records they collected during the campaign.

The information-gathering initiative began last September, when Project L.E.A.R.N. was revamped after the 2012 riot on Fleming Drive. “The intent of this strategy was to obtain reliable resident information in a controlled setting to assist us in quickly identifying residents who would be able to authorize the police to remove unwanted guests,” Duncan stated.

“Because of our experience with large groups and lawn-surfing behaviour, it is important and beneficial for the London Police Service to know who resided in each residence to be able to reliably engage the residents before the crowd swelled to unmanageable size(s).”

Though Duncan announced that information during project L.E.A.R.N. would be destroyed, unless part of an ongoing investigation, he would not apologize for the campaign. “It must never be forgotten that I have the statutory obligation to provide the citizens of London with a safe and secure environment ... I cannot and will not advocate that responsibility.”

Kelsi Smirlies, a second-year Music Industry Arts student, said she was relieved that her personal information would be destroyed. “I don't want them having all of my information,” she said.

Though Gourlay disagreed with the information-gathering methods the police used during Project L.E.A.R.N., he has been impressed when he's seen them in action dealing with students. During his ride-along with Special Constable Brent Arseneault in early September, he saw many London police on campus as part of Project L.E.A.R.N.

“They're respectful guys. I've not seen them being these big, evil guys who target students — and no one who I've met in that organization is [like that],” he said. “LPS were respectful ... It's zero tolerance, but also, they're people, and they understand.”

In terms of the fines and tickets handed out for misbehaviour during Project L.E.A.R.N., Gourlay said he thought there might be a better way to get the message across to students.

“I believe in rehabilitation, not jail or fines ... something that helps change for the positive,” he said, noting that community service or education might be a better way for students [who break the law] to learn their lessons.

Moving forward, it's clear that Project L.E.A.R.N. must evolve to suit the needs of its community. “With a lot of thought, people can come up with the answer,” Gourlay said, adding that it's a conversation that students should be involved in.

“It's true that our engagement strategy is based on past behaviours [and perceptions]. Going forward, [we're] looking to engage students in a different way,” Duncan said. “The evolution of Project L.E.A.R.N. has brought us all to a point where we must collectively step back and create a better way forward.”

With files from Stephanie Lai.