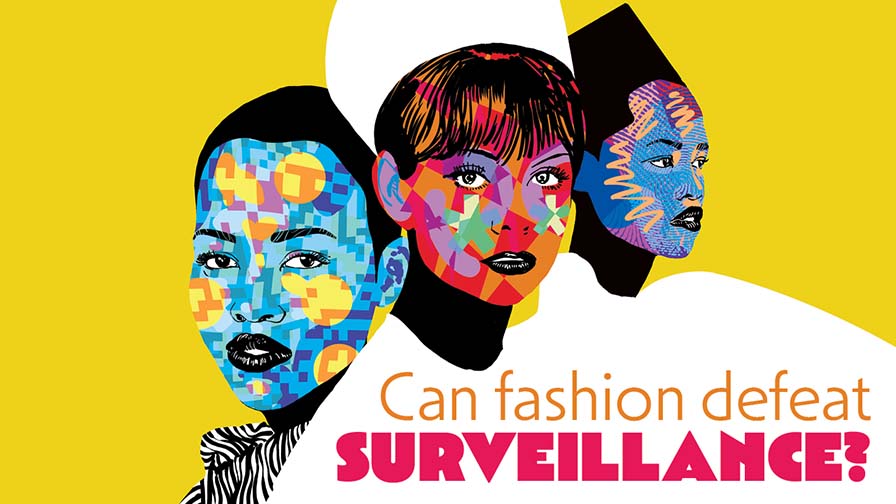

Can fashion defeat surveillance?

CREDIT: IAN INDIANO

CREDIT: IAN INDIANOThe year is 2019, and we find ourselves in Hong Kong. The idea that in a few months we would face a pandemic that would reshape the 21st century is nothing more than science fiction. Thousands of protesters have been occupying Hong Kong’s streets, in a crowd that only appears to grow. The movement started in response to a law project that would allow the government to arrange extraditions to many other countries. The protesters were afraid that a law like that could increase China’s power over Hong Kong. The project was withdrawn in Sept. 2019, but protests continued until 2020. At that point, the movement was being called a “riot” by the government and many protesters were arrested, thanks to a questionable approach by police.

As the Hong Kong protests grew, so did the media coverage. And the government response also became a public demonstration of the efficiency of their new facial recognition systems. Many of the arrested protesters were identified through those systems. I’m sure many of us remember the emblematic scenes of protesters pointing laser pointers at surveillance cameras and knocking ‘smart lampposts’ down to avoid being recognized. Although the movement, more or less, achieved its goal, it did very little to stop the advance of surveillance technology. China and other countries continue to invest tons of money in mass surveillance, and we helplessly watch cameras and smart devices multiply around us.

The comparison to George Orwell’s 1984 is almost obvious and raises a question. Are we getting dangerously close to a dystopia, or are we already living through dystopian times without realizing it? Although many countries speak against surveillance policies practiced by big-tech companies, such as Google and Facebook, it is difficult to know if those same governments are equally against similar policies that would benefit those in power and maintain the status quo. Being honest (and slightly pessimistic), I would say that it is not a matter of “if,” but a matter of “when.” It seems that, ironically, the pandemic gave us some more time. From now on, it will not be strange to see masked people around, which can conveniently come in handy during protests and political manifestations. That’s what happened during last year’s Black Lives Matter protests.

It is important to know that these kinds of technology are not a new thing. They have been around for a while; the difference is that now it’s too apparent to deny. In 2010, artist Adam Harvey created his project Computer Vision Dazzle (also known as C.V. Dazzle). His idea was to explore how pigments and shapes applied in a human face can prevent sophisticated facial-recognition algorithms from accessing their biometric profile. The idea is a reinterpretation of Norman Wilkinson’s work with camouflage. During World War I, Wilkinson, a British Marine painter, would cover military ships in dizzying stripes to warp the enemy’s perception of the size, type, and speed of their vessels. The logic of anti-surveillance makeup is basically the same.

Because we are humans, and therefore, infinitely complex beings, there are a great deal of aesthetic choices when developing this kind of camouflage. Since Harvey started his project in 2010, many other artists and fashion designers have added their take on it. If you do a quick search on Google, you will find anti-surveillance accessories, jewelry, hair styles, and more. The aesthetics of it can be a philosophical and sociological discussion by itself, but the key point is to fool the surveillance systems, which are heavily dependent on the edges on faces, which are produced by lips, nose, and eyebrows, for example.

To confuse those systems is relatively simple, and you can do it yourself. The idea is to trick the algorithms by adding man-made objects to the face to produce more edges on faces. Those objects prevent systems from finding the key edges they need to identify you. C.V. Dazzle’s website suggests that, when using makeup and accessories, you should avoid enhancers because they amplify key facial features. Partially obscuring the nose-bridge area may not let the system identify the intersection between the nose, eyes, and forehead, which is also a key feature. Symmetry is also very important for facial recognition, so developing an asymmetrical look might be helpful. You can obscure one of the ocular regions to do that, for example.

The efficiency of these techniques is very relative. Harvey proposed them in 2010 and since then, surveillance systems have advanced considerably. It is difficult to know how advanced they are, especially with the development of sophisticated artificial intelligence and neural networks. Plus, the “fashionalization” and commodification of what initially was supposed to be an apparatus for popular struggle can become an example of how capitalism is ready to sell you the revolution.

If you want to know more about Computer Vision Dazzle, you can access Harvey’s website — cvdazzle.com.