Dangerous waters for Japan's dolphins

While dolphins may be the furthest things from somewhat landlocked Londoners' minds, they have become a priority for local activist Rachel Larivee.

"The supply of dolphins, small whales, is dwindling every day. We can't keep ignoring this," she said.

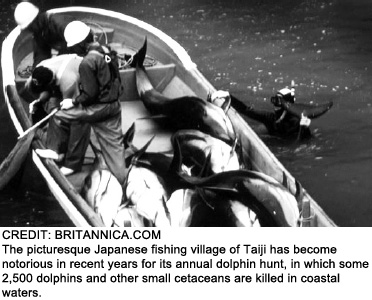

She's referring to the mass slaughtering of dolphins in Taiji, Japan. For six months of every year, about 13 boats venture into this location, as shown in the Academy Award-winning documentary The Cove.

The fishermen herd the dolphins into the coves, where large steel poles that bell out at the bottom are situated in the water. These poles create a wall of sound that throws off dolphins' sonar so they lose their sense of where they are. This creates mass panic amongst the animals. Usually this entire process takes some time, so the tired fishermen leave them there until the next day. Many of the dolphins die from the stress, said Larivee.

The dolphins that survive the night are killed using spears and knives, that don't often hit spots to kill the dolphins instantly. Some of the animals bleed for 30 to 40 minutes.

"The water completely fills with blood," said Larivee.

The strange thing is that most Japanese people do not eat dolphin meat due to its mercury content, so the killing is not for food purposes. Plus, most of the Japanese population is unaware that these killings are taking place.

Larivee, outraged at these practices, traveled to Taiji this year with other activists. While she did not go at slaughter season, she was there as they were preparing the site for it. She doesn't agree with the arguments the fisherman use as reasons for their actions.

They say they use dolphins as a food source, "which doesn't really fly with (activists)," said Larivee. Fishermen also argue that by killing the dolphins, it's a form of pest control because they dolphins eat the fish. They also claim they are catching dolphins for captivity — which doesn't necessarily follow why they kill them because dead dolphins only go for $600 on the market, she added.

The dolphin supply is currently decreasing. Before the fishermen averaged about 100 a day, now there's about eight to 30, said Larivee.

November 5 was National Anti- Whaling Day, and activists protested in Toronto. Larivee believes education is the best way to make this issue more mainstream.

"If we keep the pressure building, eventually something has to give," she said. "There's something about (dolphins) that needs to be preserved."

Those who want to get involved in the cause in London can visit Ocean Voice London's group on Facebook or contact Larivee at oceanvoicelondon@hotmail.ca.