Notes from Day Seven: "It doesn't cost anything to love our people"

The stories were heartbreaking, and more about them in a moment. Last week I attended a hearing of Canada's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) at Indian Brook, N.S. The event took place not far from the very residential school that some of the survivors at the meeting were once forced to attend.

With seven public hearings scheduled across Canada and a $60 million budget, the TRC is a national listening ear. It is mandated to provide an inclusive, victim-sensitive and culturally appropriate setting for Aboriginal people to share their experiences of the residential schools.

Survivors may tell their stories publicly or in private meeting rooms. They are not cross-examined. Their stories are only heard and recorded. The purpose of the hearings is to listen to "your truth," as TRC Commissioner Marie Wilson put it. The process is intended to help government, churches and indigenous communities come to terms with the tragedy of Canada's residential schools.

The survivors of the schools are aging, and increasingly their children are called upon to recall the suffering of their parents. Churches ran the schools for the government — implementing the government's policy of eradicating Aboriginal cultures. Children as young as four years old were forcibly taken from their homes and placed in the schools. An organizer told me that even though the schools might be located only a few blocks from the homes of Aboriginal families, family contact was forbidden for months in a row.

I heard stories of survivors being cruelly strapped for running away, for bed-wetting and for even accidentally letting any word — even a "thank you" — slip from their mouths. The children of survivors shared how their parents physically abused them because the parents had learned that beating is the main form of discipline. Some shared that the standing of parents and elders was destroyed by the schools. Others told about their longterm abuse of alcohol and drugs as a way to escape school memories.

One man reflected on the possibility of forgiveness, and how difficult it is to forgive the "black robes;" the church, the government, the media and the agencies that regulate compensation payments. "The black robes were the instruments of the government to destroy us," were his words.

There was the gut-wrenching story of a sister who was forbidden from visiting her brother in the school. She risked a great deal to sneak over to him. I heard a man tell the story, broadcast later that day, of how his hands were so badly swollen from strapping that his cousin had to feed him that evening.

One woman shared how the residential school was an evil presence. She was one of the very last residents of her school. On the day she finally left, a sister (a teacher) called out, "Wait, you forgot something," and brought out her Bible. She took the Bible from the sister's hands and threw it away. It seems that, as one survivor from PE said, "God too was a victim of the residential schools."

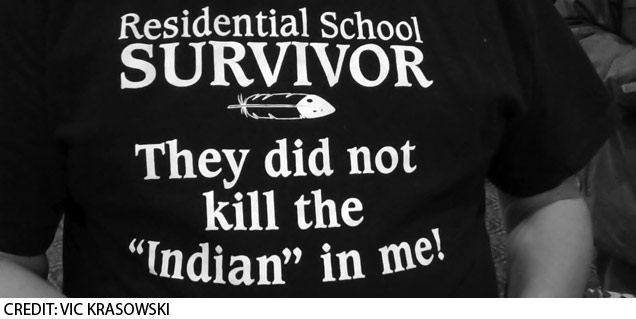

Throughout the day I began to realize that the survivors who spoke are not just victims. After all, they don't call themselves that. Their very presence at the hearing was a presence of courage. And a presence of hope. Otherwise, why bother?

A very hopeful comment was one I heard later that afternoon. It came from a survivor who had become a social worker and now uses her sensitivities to help families and youth on the reserve. She chided Aboriginal leaders who don't listen to survivors and their children. She called on them to love their struggling people. "Help will in the end not come from the government. It must come from our own people. It doesn't cost anything to love, to care, to pray for others, to treat them as human beings. It doesn't cost anything to love our people."

When she finished, I realized that this was the note on which I wanted to leave. I picked up my things and walked to the exit.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.