Allegories in Beatrice and Virgil

CREDIT: RANDOM HOUSE OF CANADA

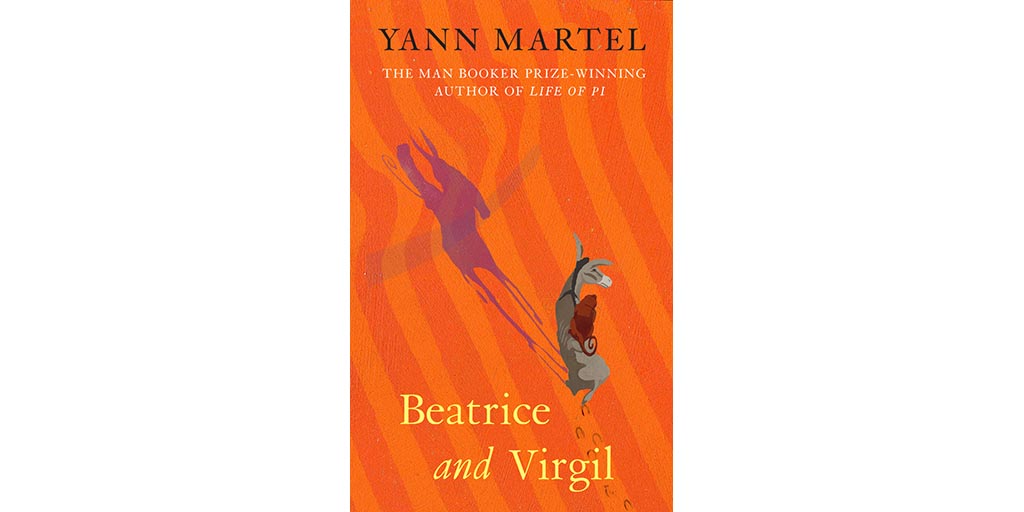

CREDIT: RANDOM HOUSE OF CANADASometimes, the simple description of a pear can be one of the most interesting parts of a book. For Yann Martel’s 2010 novel Beatrice and Virgil, this is most certainly the case, in the best way possible. Martel has written a mesmerizing story that only gains from each successive read.

Beatrice and Virgil is Martel’s third novel, following best-selling novel Life of Pi by almost a decade. It certainly shows as the book is laced with multiple literary references. If you’re the kind of person who likes quoting lines and ideas from classic novels like Orwell’s Animal Farm or Camus’ The Plague, you’ll appreciate this book even more.

The novel opens with a description of a writer that bears a striking resemblance to Martel himself, at first it seemed like it was an intro to where he came up with the idea for the story, much like in Life of Pi’s opening pages. The writer, Henry, has just gained worldwide acclaim for his previous novel and is struggling to write a novel about the holocaust for his next project. For a much-needed change of pace, Henry and his wife pack up and move to an unspecified metropolis, perhaps Boston, maybe Paris.

This is a hint of one of the book’s major theme: the distinction between truth and reality and how that can be explored through art. It doesn’t matter that we never find out where the events take place. We know that the things that take place are true, but not necessarily that they took place in that specific manner. The book serves as an allegory of sorts for the goals and struggles of the writer.

This is taken further when Henry receives a letter with a highlighted manuscript of Gustave Flaubert’s short story Saint Julian the Hospitalier. The distressed sender needs help from Henry with a play he has written.

What follows is the introduction to an absurdist play featuring a donkey and a howler monkey, written by a taxidermist also named Henry. Little snippets of the Beckett-esque play break up the descriptions of Henry the writer’s day to day life in the city, as well as his frequent meetings with the mysterious taxidermist. This creates a kind of literary fusion, part novel, part play.

The story is peppered with philosophical discussions about art and its role in society. One of the most interesting was the discussion on taxidermy, while the descriptions of the taxidermy process border on distressing, they open several interesting thoughts on taxidermy as preservation of the past.

The taxidermist writes, “When I work on an animal, I work on the knowledge that nothing I do can alter its life, which is past. What I am actually doing is extracting and refining memory from death. In that, I am no different from a historian, who parses through the material evidence of the past in an attempt to reconstruct it and understand it.”

It’s these kinds of questions that make Beatrice and Virgil such an interesting read. Although it may lag a bit in the middle of the book, the taxidermist’s play holds interest through the entire piece. If you want more of Martel’s novels, check out Life of Pi or his latest novel, The High Mountains of Portugal.