Fanshawe class finds mislabelling, lice in Ontario sushi

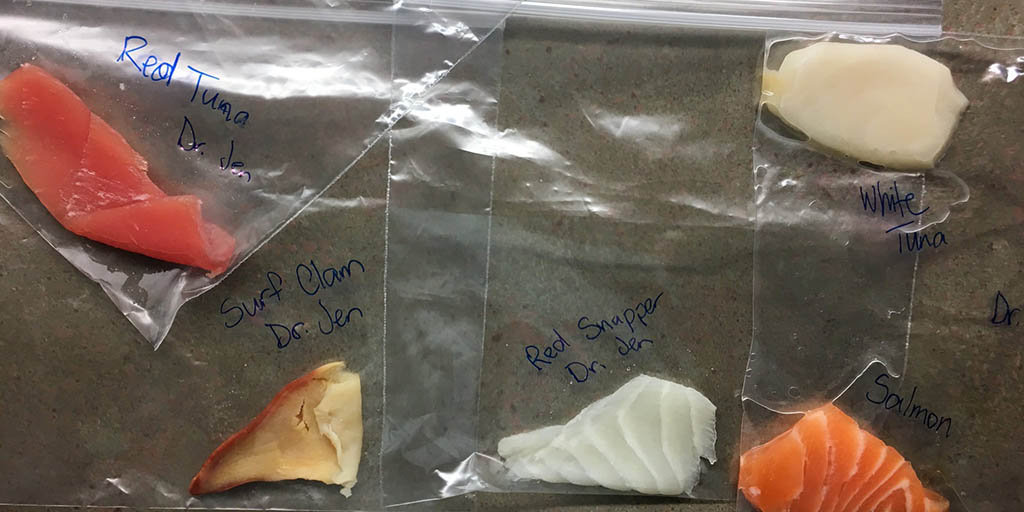

CREDIT: PROVIDED BY JEN MCDONALD

CREDIT: PROVIDED BY JEN MCDONALDA class experiment led by Fanshawe biology professor Jen McDonald found that consumers should be mindful of where their sushi comes from.

A Fanshawe biology professor has received national attention after her class found nauseating results earlier this month from an experiment that tested DNA in southwestern Ontario sushi.

Jen McDonald teaches a course in molecular biology for the College’s chemical laboratory technology program. Instead of doing the class’s typical eight-week-long capstone project, she decided to change things up and instead had the class gather sushi samples for DNA testing. The testing mirrored the same methods used by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) and U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“I thought it would be a fun way to finish off the course, by looking at the food that they eat and what it might actually be, whether it's labelled correctly or mislabelled,” McDonald said.

The class brought in 16 total samples of fish from all-you-can-eat buffet-style restaurants, as well as grocery stores, in London, Mississauga and Muskoka. Some were pre-packaged and frozen and some were fresh.

McDonald found a kit through a biotechnology company that allowed students to extract and analyse the fish’s barcoding gene. The samples were then sent to Western University, where 12 were successfully amplified at a sequencing lab. Of those 12, nine gave clear sequence samples.

Although McDonald knew “fish fraud” is a regular trend in the industry, she was still surprised by what the class discovered.

“We were expecting about a 50 per cent mislabelling rate which is pretty standard in Canada based on previous studies,” she said, “but instead we found more like a 75 per cent mislabelling rate.”

Testing results revealed that only two of the fish had been properly labelled.

Others were not as they appeared to be.

Tilapia was being passed off as red tuna, perhaps through the use of food dye. Samples of rainbow trout turned out to be coho salmon and Atlantic salmon, and Atlantic cod had been labelled as Pacific cod.

White tuna samples were actually escolar, which contains an indigestible oil that can have a laxative effect on humans.

Perhaps most disturbingly, one of the fresh salmon samples, taken from a grocery store, had tested positive for body louse, similar to head and pubic lice.

“We have no way of finding out whether that came from the grocery store, whether it came from the supply chain, whether it maybe even came from the original processing plant where they take the whole fish and turn it into pieces that you would buy at the store,” McDonald said. “We have no idea where that little bit came from, but that was the cleanest bit of DNA that came out of that sample, was not for salmon but was instead for body lice.”

McDonald’s Tweets of the experiment caught the attention of national news, sparking a conversation about the prevalence of food mislabelling and its possible dangers.

She said that aside from white tuna being escolar, the biggest risk lies in a person accidentally eating a food that causes an allergic reaction. Otherwise, consumers shouldn’t be surprised to learn that they have most likely eaten mislabelled fish at some point.

“[The average person won’t] notice a difference between trout and salmon,” she said. “You've probably been eating that mislabelled fish for your entire life and maybe for some people they don't even really know what salmon actually tastes like.”

She added that the trend of mislabelling perhaps points to the decline of certain fish worldwide, such as tuna, red snapper and cod.

“If we can pass off a substitution for a cheaper more abundant, maybe even farmed fish, maybe we should be doing that,” she said. “If none of us can tell the difference between that and tilapia, maybe we should all just be eating tilapia instead.”

According to McDonald, the biggest takeaway from the experiment was for consumers to be more mindful of where their food comes from. One way consumers can do so is to make sure the Marine Stewardship Council has certified their fish sustainable.

McDonald said that despite the experiment, her personal love for sushi has not been affected.