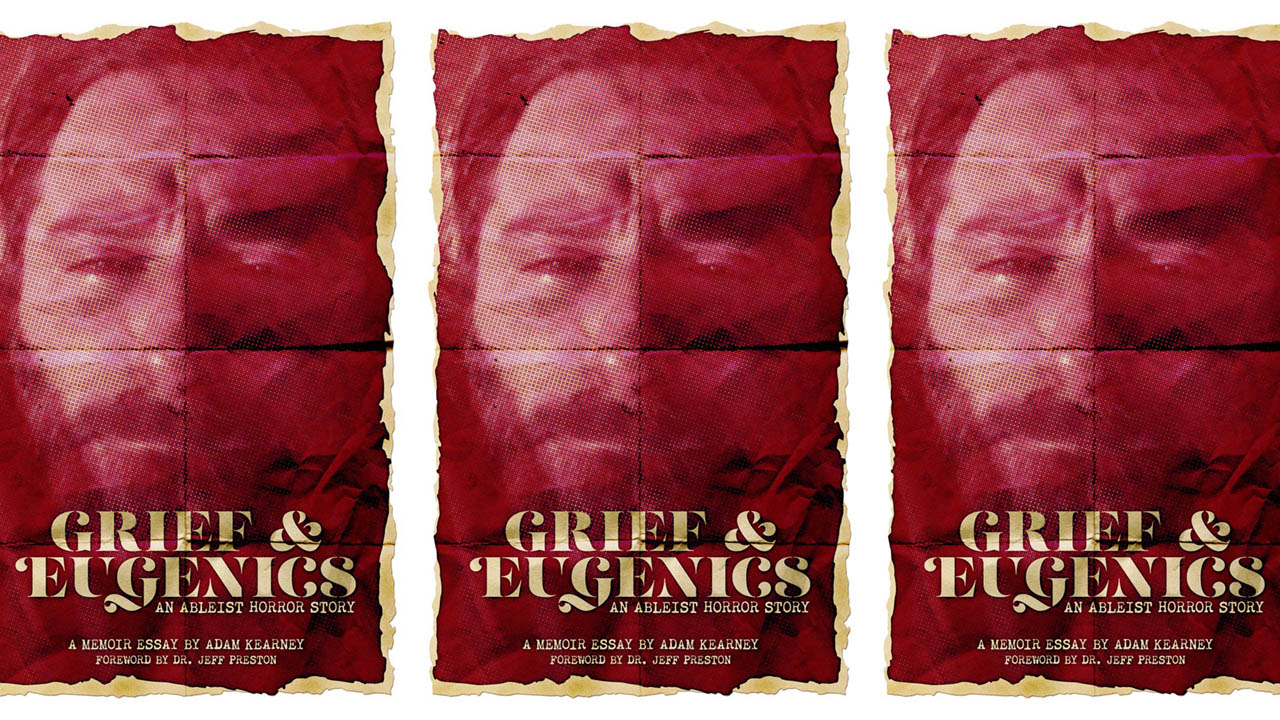

Grief & Eugenics: An Ableist Horror Story, Part One

CREDIT: COURTESY OF ADAM D. KEARNEY

CREDIT: COURTESY OF ADAM D. KEARNEYLiving with disabilities can be an isolating experience, but people with disabilities have existed all throughout history.

This article is Part One in a series of excerpts from Fanshawe grad Adam D. Kearney’s essay, Grief & Eugenics: An Ableist Horror Story.

Foreword

“It is impossible to see reality except by looking through the eyes of the Party. That is the fact that you have got to relearn, Winston. It needs an act of self-destruction, an effort of the will. You must humble yourself before you can become sane.”

– George Orwell, 1984

Disability can be isolating, a reality so taken for granted it might not require exposition. We understand that disabled people are isolated physically by “normative” design standards that do not account for different bodies. We talk about how disabled people can be isolated economically by education and work systems designed for neuro-specific function. We explore how disabled people are isolated culturally with disabled characters often existing as plot devices, something to be solved or resolved by the nondisabled main character. Even our lived experiences are held at a distance, with disabled people thought to be “inevitably exposed to a discrimination that cannot be shared,” in the words of psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva in Hatred and Forgiveness (2010). But there is another experience of isolation that is not as widely acknowledged: our isolation from each other and ourselves.

Many of us are born into nondisabled families, with parents or siblings who have no comparable experience. Many of us, especially those of us in rural regions, will grow up in classrooms dominated by nondisabled students and teachers. After graduation, we will often be the only, possibly even the first, disabled person in our workplace. While we may be welcomed in these spaces, once proving an appropriate proximity to normalcy, this acceptance can also feel incredibly fragile. At times, it can feel like our acceptability must perpetually be proven or we risk (r)ejection, back to the shadow realm of disability. The outcome is spending much of our lives relating and responding to the able-bodied world, seeking access to a community that hinges on our capacity to not be disabled. As Erving Goffman notes in Stigma (1963) this might be managed through things like self-deprecating humour or skill mastery but, for others, it can mean a complete rejection of the disabled community, driven by a belief that to be in community with other disabled people only confirms one’s “spoiled” status.

All of this is to say that when one spends most of their life living under the watchful eye of the Normalcy Party, it is difficult not to internalize at least some of the doublespeak.

For academics like Fiona A. Kumari, this is the insidious nature of internalized ableism. If every person you encounter is convinced that disability is a tragedy, and offer praise when they “don’t even see you as disabled,” it should be no surprise when people begin to see disability as a negative asterisk affixed to an otherwise “normal” subject position. We are asked not just to reduce disablement from our subjectivity but to wholly erase it from our existence. One of the cruelest demands of internalized ableism is mandatory self-immolation: a perpetual need to burn off the contaminated bits of us to leave fertile ground for a “normal” self to emerge. More than just being compelled to able-bodiedness (see Robert McRuer), we are all indoctrinated to both desire and be willing to sacrifice everything, even our very identity, for a mere chance at grasp the gold ring of normalcy.

Or, put another way…

“Four wheels good, two legs better! All animals are equal. But some animals are more equal than others.”

Dr. Jeff Preston, PhD

Associate Professor, Disability Studies

A brief history of disability & grief In the beginning, there was disability. There just was. Both congenital (born with) and acquired disability happen naturally. You might be shocked to hear that they happen outside of the Human race as well. We have found some very unique ways of contextualizing it. However, we have a habit of fearing, vilifying and demonizing what we do not know or understand.

“People of Akwesasne explain, without apology, that it isn’t disability which makes people different so much as it is the assumptions and misunderstandings that go along with it. Despite the tireless efforts of family and volunteers, many Canadians with disabilities still face a life of isolation and dependence. Too often they feel shut out of even routine daily concerns, like shopping or visiting friends and neighbours. Attitudinal barriers, more than anything else, prevent persons with disabilities from contributing to and benefiting from the richness of community life. Simply put, there is a lack of awareness and understanding for the potential and the aspirations of persons with disabilities.”

From the book TE-WA-KWE-KON: Together As One.

I feel like I need to state that in no way am I a sociologist, historian, psychologist or in any way a certified anything (asshole maybe). What I do have is my life experience. I was diagnosed shortly after birth with a genetic disorder called Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI), more commonly known as Brittle Bones disorder. I stopped counting fractures and surgeries when the numbers hit the high 80’s before I became a teenager. I largely use a wheelchair to get around these days, though if I am fracture free I will also use a walker for those hard to reach spots (stairs, sand and grass oh my). My life has taken many unexpected twists and turns over the years, leaving a lot of wreckage, but mostly grief in its path. Since getting sober a couple of years ago I have been putting a lot of work into picking up the pieces of my life and trying to figure out just how I ended up in the situation I find myself in. It has not been easy work. I know that I have so much yet to sort out, build upon and learn.

To be continued…

This memoir essay was published as a zine in Jan. 2023. If you enjoy it and feel you would like to support the author, you can find a pay what you can PDF or purchase a physical copy at handcutcompany.com.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.