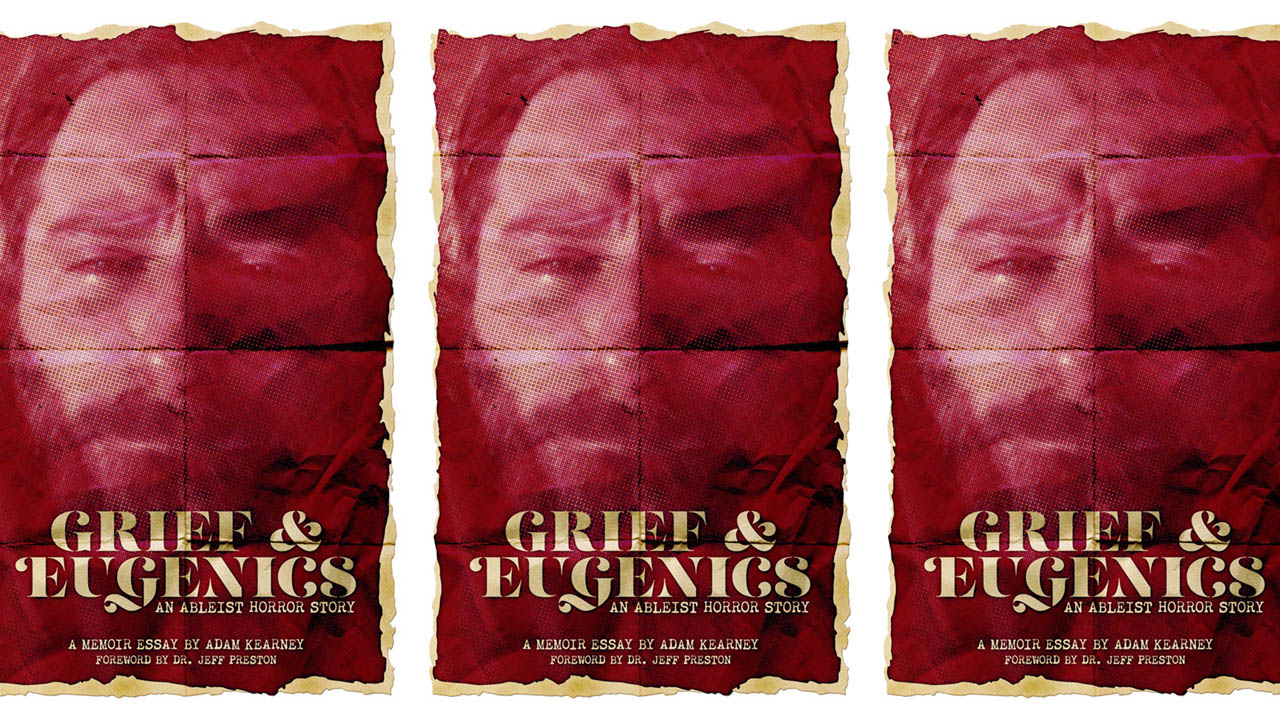

Grief & Eugenics: An Ableist Horror Story, Part Three

CREDIT: COURTESY OF ADAM D. KEARNEY

CREDIT: COURTESY OF ADAM D. KEARNEYPeople with disabilities carry an inherited grief with them through their lives.

This article is Part Three in a series of excerpts from Fanshawe grad Adam D. Kearney’s essay, Grief & Eugenics: An Ableist Horror Story.

Societies have long dealt with situations involving people with disability through a lens of negativity, as though it was a problem needing a final solution and ignoring the nuance and individual subtlety of disability. If you aren’t Jesus and magically curing folks isn’t an option then what do you do? Institutionalize, sterilize and exterminate in a practice known as Eugenics.

When individuals were not able to be cared for at home by family, institutions were set up to house people with disability en masse. Unfortunately, I am sure you can imagine the kinds of conditions folks were forced to live in. Things were not much better if someone lived at home with family; as they were essentially on house arrest and not allowed to socialize with the common public.

Punishment was thought to be appropriate for individuals with physical disability should they leave the house or escape the prison-like institutions in 1729 England. Eventually America got wise to this idea and in 1881 started passing what are now referred to as the Ugly Laws. These laws were specifically targeted at impoverished and/or disabled community members by either incarcerating or fining them for being in public. For example Chicago passed this into law:

“Any person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object, or an improper person to be allowed in or on the streets, highways, thoroughfares, or public places in the city, shall not therein or thereon expose himself or herself to public view, under the penalty of a fine of $1 for each offense (Chicago City Code 1881)” ($1 in 1881 is roughly $30 in 2023).

Often the people who were arrested were then shipped off to poor houses or work farms, to ensure they remained segregated.

America quickly became the shining example to the world of how to manage populations that were deemed inferior. So much so that a young rising power in Germany looked to the lessons Uncle Sam had to offer to start writing their own legislation. In 1933, Nazi Germany passed the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Defective Offspring based on laws already written by the Eugenics Record Office in the United States of America. From this law it is estimated that 360,000 people with diagnosis ranging from schizophrenia to chronic alcoholism and other forms of social deviance were sterilized between 1933 and 1939. At which point the government passed Aktion T4 which authorized the involuntary euthanasia, or mercy killings as Goebbles would phrase it in his propaganda films, for people with physical and mental disability. Although largely undocumented, people with disability would be the first victims of mass murder by the Nazis. By the end of the war they would go on to kill an estimated 275,000 to 300,000 people with disability.

Though social revolutions have happened around the world (the Ugly Laws remained on the books until 1974 in America) to help give disabled folks rights, forced institutionalizations and sterilizations are still happening to this day. Just this past November, after 10 long years of fighting, a woman in Halifax was able to move out of a Long-Term Care facility and into her own community. If you are looking for a real horror story google what the “Ashley Treatment” is. It symbolizes the atrocities bodies with disability have had to endure to make non-disabled people more comfortable.

This is the inherited grief that people with disabilities carry with them as they move through their life, forever looking for an escape from systems that impose suffering upon them. Some folks find the courage to advocate for systemic change. Others try to find serenity in accepting the fates forced upon them. Myself, I took another path, which led me to discover a grief few people have experienced. My only hope is that by sharing my experience it may help other people, whether that be to connect, share, be seen, and/or heal.

To be continued…

This memoir essay was published as a zine in Jan. 2023. If you enjoy it and feel you would like to support the author, you can find a pay what you can PDF or purchase a physical copy at handcutcompany.com.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.