The end of the world?

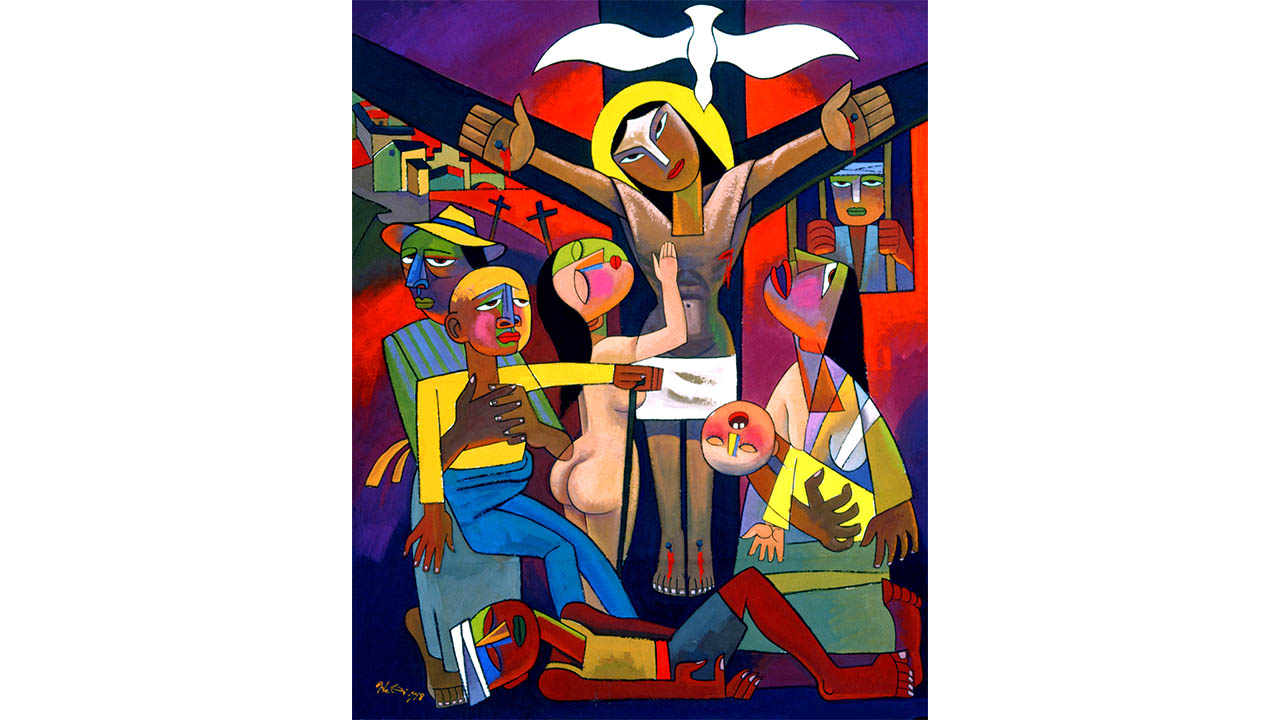

CREDIT: USED WITH PERMISSION FROM HE QI

CREDIT: USED WITH PERMISSION FROM HE QIThis Easter, remember the impact of Jesus' death on humanity, which brings God's forgiveness, healing and peace to the world.

I began my last article by saying that the two most important days in the world-wide church calendar are coming up.

They are Good Friday and Easter. A slight correction: Western churches and Eastern churches have different dates for both those days.

So, for example, The Roman Catholic Church, a Western church, has different dates for Good Friday and Easter than The Russian Orthodox Church, an Eastern church. However, the dates are always close, and I am quite sure that nothing hangs on the differences anyway.

One of my go-to images at this time each year is by artist He Qi. He Qi was born in China and grew up during the infamous Cultural Revolution, 1966-1976. The university in which his father was a professor of mathematics was closed by the government. He Qi himself was sent to a labour camp for “re-education.” While he was there, an older friend taught him how to paint. This resulted in an event that changed He Qi’s life.

He stumbled across an image called Madonna by an Italian artist of the 1500s, Raphael. (Raphael painted more than one Madonna.) The painting depicts the mother of Jesus, Mary, with her child. He Qi tells about the sense of peace he experienced at seeing the image (YouTube video entitled “He Qi — The Peaceful Message: In His Times”). That painting, and the feeling of peace it provoked in He Qi, contrasted sharply with the violent ideology of Marxist China.

Since those years He Qi has earned a PhD in fine art and dedicated much of his life to painting the stories of the Bible so that the Chinese may be exposed to the Gospel (literally “Good News”) of Christ. His work has elements of European modern art, Chinese art, and folk art, making it accessible to viewers from Hamburg to Beijing to White Horse.

The image by He Qi that I am including in this article is titled, The Crucifixion. Red is a dominant colour, signifying judgement and pain. It resonates with the disturbing image at the centre of the work. There we see Jesus Christ crucified. (Crucifixion was common in Jesus’ time.)

The crucified Christ is depicted, firstly, in the four accounts of his death in four different books collected in the Bible. Secondly, his death is presented in countless paintings and films. Nearly all of the depictions bring to mind the suffering of Christ for the sins of humans everywhere. He takes upon himself the penalty for — he attracts onto his own self God’s judgement upon — greed, murders, thefts, judgementalism, deceptions and all other sins.

Some people, in an attempt to do justice to the global impact of the image of Christ’s death, claim that it is the clearest representation of the archetypal scapegoat and the sacrificial lamb. Both of those are clearly presented in the pre-Jesus parts of the Bible, in the Jewish tradition. And Jesus accepted them as defining much of his identity and mission. He especially saw himself as the “lamb of God.”

However, he did not see himself as a mere symbolic representation. He saw himself as the ultimate sacrificial lamb and scapegoat, the one provided by God.

The followers of Christ all over the planet see him that same way. In other words, Christians do not have faith in an archetypal, symbolic figure. They have faith in the ultimate sacrificial lamb.

But the larger focus of this painting is not the actual suffering of Jesus. Rather, it is the effect that his death has. It brings God’s forgiveness, healing and peace to the guilty and broken people of the world. We see a man bringing an unwell adult, likely his son, to Jesus. We see another figure at the bottom of the painting, severely injured or ill, perhaps dead. We see a mother bringing her child who appears, if not dead, very close to being dead.

Holding onto Jesus is a naked woman. This is not meant to suggest any kind of sexual encounter. Rather, it recalls that in the biblical accounts of Jesus, women who were sexually exploited were not discarded by Jesus. He supported them and gave them a new start. Also, in some of the stories of Jesus we meet “sinners.” This was most likely a discreet — but very well understood — way of referring to prostitutes.

In the background we can see a collection of dwellings, bringing to mind not only that Jesus died just outside the walls of Jerusalem. The collection also reminds us that Christ came for all persons and went out to meet them where they lived. The Son of God travelled among the Israelite towns and cities of his time.

On one side of Jesus we see a figure behind bars, indicating Jesus’ interest in people convicted of crimes. He spent his last night in a police custody of sorts, being interrogated under torture. And on the other side, there stand two crosses, recalling that Jesus died with one offender on his right and another on the left.

Jesus Christ suffered and died in order to bring God’s forgiveness, peace and restoration. His arms are outstretched to embrace all people in our troubled world. He Qi has painted the cross in the shape of a 1960s peace symbol. Above, he has placed a white dove, a biblical symbol of the Spirit of God. The Spirit is not only a source of God’s power. He also turns the hearts and minds of people towards the bringer of peace, Jesus.

The days of our wars, social media quarrels, and domestic abuses are numbered. Jesus’ death opens the way to renewal for us and our world. That is why Good Friday is called “good” even though it commemorates a horrific death. And it is why, on Easter Sunday morning(s) there will be music, prayers, and celebrations pouring out of church buildings and Christian homes all over the planet.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.