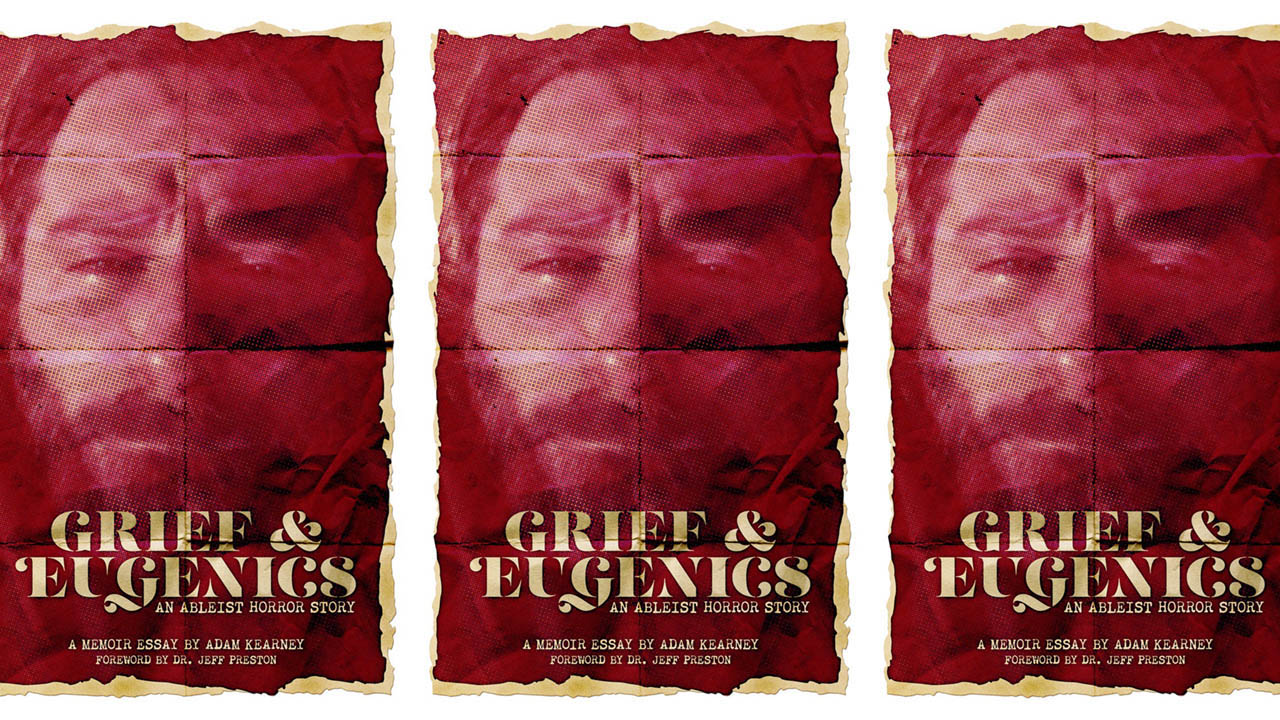

Grief & Eugenics: An Ableist Horror Story, Part Five

CREDIT: ADAM D. KEARNEY

CREDIT: ADAM D. KEARNEYA deeper look into navigating friendship as a person with a disability.

This article is Part Five in a series of excerpts from Fanshawe grad Adam D. Kearney’s essay, Grief & Eugenics: An Ableist Horror Story.

As we got older we talked about bullies, politics and religion. One day we ended on the topic of mortality and it terrified both of us. I mean, it terrifies most people, it should, but we each had a unique relationship with it. Growing up my mom would come into my school and do talks about how my OI diagnosis affected my life. Broken bones, different rodding surgeries on my legs, and shortened life expectancy. That last one has haunted me my entire life. Imagine sitting in a room full of your peers being embarrassed by your mom explaining exactly how you are different from the rest of them, and then having that nugget dropped on you without warning. It really festered in me until one night at a neighbourhood pool party I worked up the nerve to ask one of my parents what happened when we die. I think this really took them back, as they deferred the question to our neighbour who is a nurse. She managed to gently explain how eventually our bodies stopped working, which didn’t really satisfy my young mind. I wanted to know what happened after. She told me that no one can really answer that question because once you are dead, you are not able to come back to tell anyone what it is like. I slowly put a swimming mask on as I started to cry and put my head half way under the water so I could see above and below the water at the same time.

I shared this story with Josh during one of our late night chats. He came from a rather religious family and I think had a moment of pause about his view of an afterlife. If it did he really didn't focus on it, he was more concerned about the window of time he had left. At that time, the life expectancy for someone with a diagnosis of duchenne muscular dystrophy was late teens to early twenties. Josh’s brother David also had chronic health issues, and Josh told me it was a constant reminder of how fragile his health could and would eventually be. We were all barely into our double digits and we were being told that the writing was already on the wall for us. There was still so much we wanted to do with our lives, after all we still didn't know what boobs felt like!

This was something we both had in common, a fantastic sense of humour, and looking back now it was obviously our preferred coping mechanism. No matter how dark or sad our conversations would get, generally one of us would read the room and crack a joke to lift our spirits again.

Our friendship wasn’t exclusive to camp; we had traded phone numbers and addresses and we stayed in contact all year round. Letters, but more often phone calls, would happen regularly. As well, the camp we went to offered a respite program once a month during the rest of the year, where parents could drop their kids off for a weekend. More often than not, it was the kids at camp that needed a break from home rather than the parents needing a break from them.

Eventually, because I have the privilege of being able to handle all my own personal care, an opportunity arose. I was able to apply to become a Leader In Training and make the transition from camper to potentially becoming a counselor. I had already been helping my friends when and where I could with small stuff throughout the day, like during programs and in the dining hall. Best of all, it seemed like a great chance for me to spend the whole summer away from home and at camp. Camp was a place where it seemed like my disability was minimized almost to the point where it didn't exist, unlike at school where I was being bullied more aggressively.

Looking back now, this was a period of my life where things shifted in a very drastic way, though it all unfolded so slowly that I didn’t realize what was happening. When I became a counselor I started working at a different camp, so I wouldn't have to be providing personal care to my friends. This took me out of my last peer group of folks with disability. Though, there were a couple of other counselors with disabilities, and I did stay in contact with Josh and a few other friends. My environment had drastically changed, and no one at the new camp knew the old camper version of me.

During this transition a couple of specific things occurred. First, I had my first relationship with a nondisabled woman. I am now ashamed to admit just how much it meant to me at the time. To my teenage mind dripping with internalized ableism it was like the guy getting the girl at the end of Revenge of the Nerds. The other thing that started to happen was friends and former fellow campers were dying due to complications related to their disability. This was so incredibly hard to process. These friends I had grown up with, who were the same age, were now gone because of disability. It felt like the clock was ticking for me, so I doubled down, and tried to disassociate from my disability and the disabled community even more.

Over time I spoke to Josh less and less, and by the time I was off to college we were hardly in touch. I was too busy partying and trying to fit in to maintain our friendship. This was also around the same time I would start to grimace when someone would suggest I need to meet their other friend who also uses a wheelchair. It’s pretty damn presumptuous for someone to assume that disabled folks need to meet their other disabled friend (would you do this with your BIPOC friends?), but my immediate rejection of the idea should have been just as troubling. My thought was always “how dare you clump us together like that.” Hearing friends tell me “I don’t even see you as disabled” was me trading in my participation ribbon for a first place ribbon.

This went on for about twenty years. Roughly the same amount of time that I had last talked to Josh. Now here I am, over two years into my sobriety, having put a lot of work into my identity as a person with disability. Trying to process and move beyond my ableist views, and unpack all my lovely internalized ableism. The facebook message that one of my oldest best friends is on his deathbed shocked me in a way I didn’t anticipate. I didn't know what to say. How do I even begin to apologize for ghosting Josh on our friendship? How do I explain the world of pain I caused myself by turning away from him and a community that meant so much to me at one point? The community that helped me navigate some incredibly tough times growing up. Not only was I riddled with questions like these, I was also overwhelmed with anxiety and pressure to prepare for the holiday market season. Looking back, I am surprised it didn’t make me relapse.

I realized that apologizing at this point of Josh’s life for being a truly shitty friend would only be self-serving to me. I decided I wanted to share a few cherished memories that have stayed with me. That he was one of the greatest friends of mine. I was in the middle of crafting my message to Josh when the same friend who reached out before sent me Josh’s obituary. I read it as tears rolled down my face. The picture they had chosen to go with it featured the same smile I remembered from all those years ago. I can still hear his childish laugh in my head. It both makes me cry and warms my heart at the same time. I had been through enough loss to understand that this is what grief can feel like. Both good and bad held together closely in my heart.

To be continued…

This memoir essay was published as a zine in Jan. 2023. If you enjoy it and feel you would like to support the author, you can find a pay what you can PDF or purchase a physical copy at handcutcompany.com.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.