Sustainability Today: Jolt from mounting e-waste

CREDIT: FANSHAWE SUSTAINABILITY

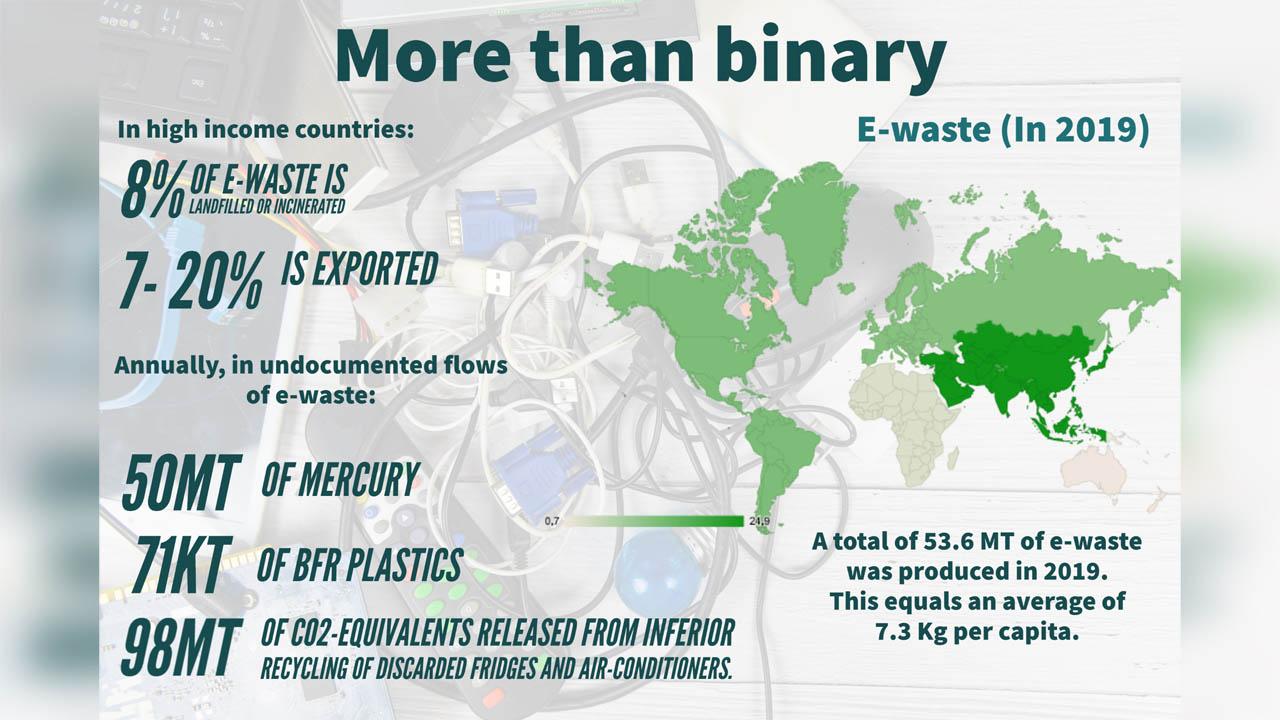

CREDIT: FANSHAWE SUSTAINABILITYAccording to the Global E-Waste Monitor 2020 report, the world generated 53.6 million metric tons of e-waste.

Don’t we all love electronic gadgets? Every year we see the release of new and improved smartphones, laptops, tabs, and more. The market for electronic and electrical devices is ginormous. At home, the kitchen is incomplete without appliances. At work and school, anything ‘smart’ is a must-have. Starting in the mid-20th century, with the invention of the transistor, silicon- chip-driven gadgets have made a bigger impact on our lives, now more than ever.

With the impact comes the aftereffects. Electronic gadgets are often discarded, replaced by a swanky and new model. According to one statistic, the average lifespan of a smart phone is four years, and that of a computer-laptop three. This means that we produce a lot of e-waste and a simple exercise to gauge that amount is to go through the timeline of electronic and electrical gadgets you have owned— from the first Walkman (PS: no offense if this sounds old) to the smartphone that we currently own. Let us take a step away from nostalgia and think about what happened to those gadgets. Where are they now? We may find them tucked away in the attic, but most are likely in a landfill. According to the Global E-Waste Monitor 2020 report, the world generated 53.6 million metric tons of e-waste— about the same weight as 412 CN towers— in 2019 and “only 17.4 per cent of this was officially documented as properly collected and recycled.”

Why does any of this matter? Components of e-waste contain harmful substances that degrade the environment, such as Hydrofluorocarbons (refrigerator coolants), and elements such as lead and mercury, which affect the health and wellbeing of all living things. A World Health Organization (WHO) report states that 12.9 million women, who work in the informal waste sector, and their unborn children are at risk due to potential exposure to toxic e-waste.

The e-waste conundrum has also exposed the inequities in the world. Waste from developed nations is shipped to developing countries, where it is processed by people who have limited to no access to personal safety equipment. Exposure to toxic materials in e-waste such as lead and mercury can have detrimental effects on health, especially that of children whose developing organs are vulnerable to such exposure. According to the WHO, there are 18 million children and adolescents (aged five-17 years) engaged in e-waste processing activities. With little regulation, these e-waste processing grounds, which are already health-risk zones, become a haven for exploitation.

What can be done?

The issue of e-waste is intricately linked to the UN Sustainable Development Goals six (Good health and wellbeing) and 12 (Responsible consumption and production). Also, there have been international conventions such as the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, which aims at “suppressing environmentally and socially detrimental hazardous waste trading patterns.”

On the production side of trade, there is Electronics Product Stewardship Canada (EPSC), which “represents the interests of electronics manufacturers for innovation in enhanced end of life solutions for electronics products in Canada.” In its 2021 report, EPSC stated that “households now produce about 10 per cent less electronic waste by weight than they did at their peak in 2015.” Locally, there are many options to choose from when considering safe disposal of e-waste.

Fanshawe recycles its e-waste with the help of TechReset, an e-waste disposal company. At main campus, there are crates in the receiving area for e-waste to be properly disposed of. Also, empty toners and ink cartridges, e-waste including phones, laptops, computers, batteries, and power cords can be dropped off in the collection bins at the Student Centre and the Bookstore.

In 2021, the college community generated 6.6 tons of e-waste, 99 per cent of which was diverted from landfill through the e-waste program. Most discarded e-waste can be reused. The college organizes asset resale events where old, functioning electronic devices are sold at a lower price, giving them a second chance to complete their life cycle before being recycled.

We need to start somewhere to mitigate the issues and a good place to do would be by following guidelines for proper disposal, donating, or selling old equipment and being mindful of the said things when buying electronic goods. Our future surely will be a digital one, where everything is available on top of fingertips. This utopia can only come true if we act now, follow the principle of Three Rs(Reduce, Reuse and Recycle) and choose sustainability— It’s for and about you, me and us.

Contributed by Fanshawe Sustainability